How To Benefit From the Nature on The Nomad Way Turkey

November 17, 2020

Interact With Locals, Collecting Memories on The Nomad Way – Turkey

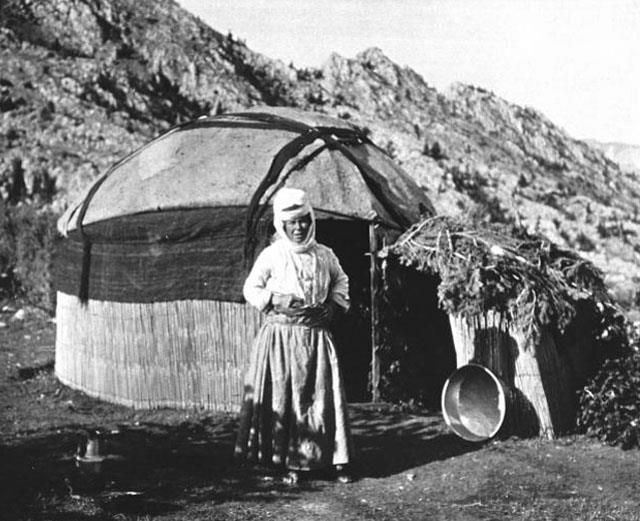

November 17, 2020Turkmens of Anatolia have used the black nomadic tent for more than 300 years. Before the Ottomans banned nomads to animal husbandry in the plains of Anatolia, the nomads had millions of sheep and used round wool felt tents that they had brought from Central Asia. For the new lifestyle squeezed between mountains in summers and narrow seashores during winters, goat herds as livestock and rectangular goat hair tents rather than round felt tents were more suitable.

Afshar tribeswoman Tomarza Kayseri Central Turkey 1909, photo courtesy Gertrude Bell

The goat hair nomadic Turkmen tent is made of black goat hair, not only because most Anatolian goat breeds have black hair, but also the black color causes an interesting entropy rule, which works to cool down the temperature of the interior of the tent during the summers and heats the inner temperature during the winter.

Goat hair black tent belonging to Sachikara Turkmen tribe. Kahramanmarash, Eastern Turkey, 1980s, Photo by Josephine Powell, Suna Kıraç Foundation

Speaking of the goat hair, one should explain how it is turned into fabric. Shorn once a year from the back of goats by men, the hair is combed and spun at the hands of Anatolian Turkmen nomad women, and woven in warp face technique, widths of 60-70 cm narrow panels of several meters long. The panels are sewn together to form the tent fabric.

An Anatolian Turkmen lady combing goat hair to make nomadic tent Olukbaşı Village, Bozgoğan, Aydın City, Western Turkey 2016

Goat hair spun with big spinning wheels Olukbaşı, Bozgoğan, Aydın, Western Turkey 2016

Dursun Öztaban weaving an Anatolian Turkmen black tent from goat hair, Olukbaşı village, Bozdoğan, Aydın, Western Turkey, 2015

The fabric is impenetrable by animals and insects which have scales under their bodies. Snakes, scorpions, centipedes, spiders, and other venomous creatures cannot walk on it because the hairs going out of the surface of the fabric form a very spiky area which irritates their scales and prevents them from entering the openings between the loosely-woven warps and wefts..

The tent fabric is a coarse weaving and can weigh around between 90 or 150 kg, depending on the dimensions of the tent. The smallest dimension would be 3 meters by 4 meters, the biggest would be 6 meters by 8 meters, which would be the maximum weight that a camel can carry in its back.

Loading the camel with the tent fabric, Sarıkeçili Turkmens, Mersin, Western Turkey , 2015

The Anatolian Turkmen nomad black tent has a roof in a gabled form which directs the rainwater to flow down without penetrating the inner part of the tent. The goat hair warps and wefts absorb the rainwater and puff up, and the small holes between warps and wefts are completely closed. But on a sunny day, the small holes of the fabric aerate the inside of the tent and also provide a net view from which the outside can be seen more or less, so a person passing through the encampment area can be easily seen and recognized, but from the outside, it is impossible to see the inside of the tent.

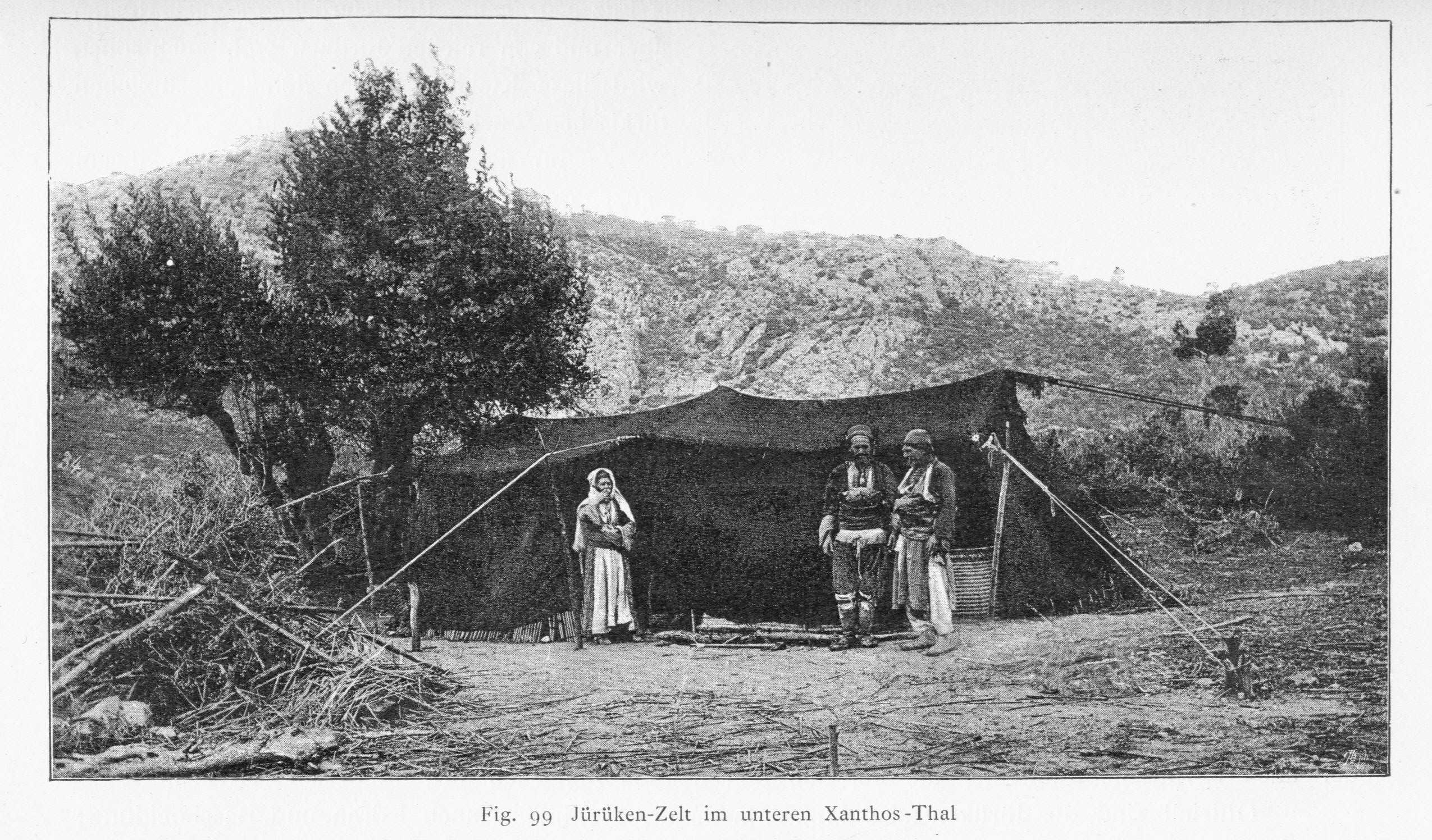

Anatolian Turkmen Black Tent, Xanthos, Sout-Western Turkey, Thal Von Luschan 1889

The tent has a rectangular shape and four walls under a gabled roof. All of the walls and the roof itself are fixed to each other by the help of wooden sticks more or less in the dimensions of a small pencil, and are dismountable. The roof is erected onto a tree or four central poles placed in the central axis along the length of the rectangle tent area. The small poles on the long edges hap help to hold the walls up, or sometimes there are no small side poles and the walls are fixed to the edges of the roofing textile by the small wooden sticks. All of this construction is fixed to the ground by eight ropes, four from the corners, and four from the middle point along the width and the length of the tent.

The nomad way to fix the tent wall to the tent ceiling

Tent poles in the middle of the side walls

There is no door, but an opening of one wall of the tent used as a door, and this opening faces towards the south or the east to have more sunlight inside of the tent.

A reed screen or a long woven reed mat is wrapped to block the wind and to pull the tent fabric to the inside area of the tent. Also, these reed screens or mats provide a place to put one’s back and shoulders while sitting.

Anatolian Turkmen Black tent view from the inside with the reed screens placed on the edges

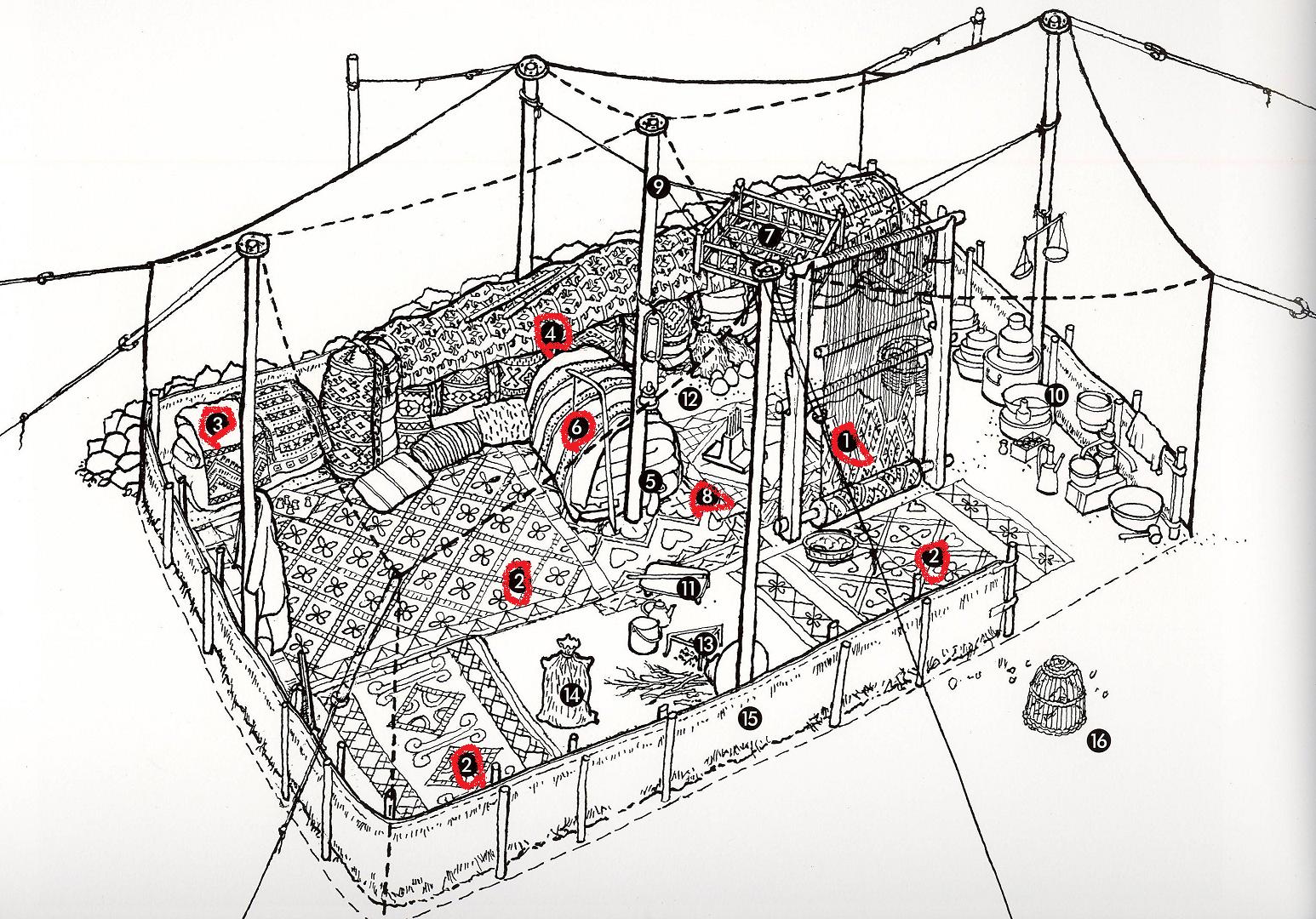

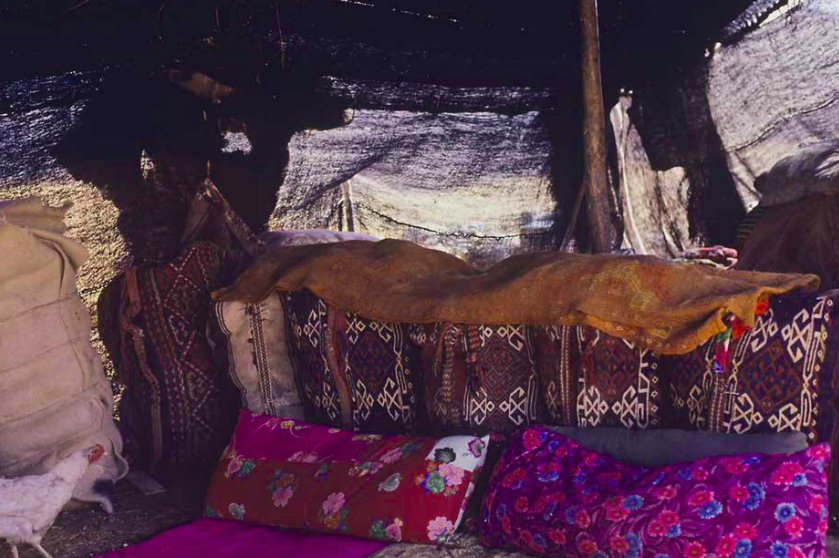

The inside of the tent is decorated and arranged according to tradition-based functionality. The door is always at a corner of one of the long edges. By entering the tent, on the left-hand side there is the fireplace and the small kitchen, which serves to cook and to heat the inside of the tent if necessary. On the right-hand side, there are wheat, flour, and bulgur sacks. On the opposite side, which means a bit further in the tent and on the right-hand side, are beautiful ornamented sacks which hold the personal belongings of the family members. The guests are invited to sit further on the opposite corner of the tent, the farthest point to the door, to protect them from whatever enters from the door. This corner is the most colorful and ornamented place of the tent. On the left side of the “guest sitting area” the tent owner sits and monitors everything going on in the tent.

The inside of the Anatolian Turkmen Black Tent

The nomads believe in a legend about the Turkish tent and the Prophet Mohammad. The Prophet Mohammad had a follower who came to settle in Makka from Turkistan. One day he brought a round felt tent to the Prophet and gave it as a present by saying it will be cooler than any other domicile in the desert conditions. The prophet witnessed the fact and prayed “May whoever living under this tent and whoever constructed it be given the blessing and the abundance of God!” It is believed that from that very moment Turkic tent holders have never been in misery or poverty or starvation. So when a Turkmen nomad, whether Anatolian or Central Asian, makes a sacrifice and slaughters a sheep and distributes the cooked sheep to his/her neighbors and relatives for charity, it is to celebrate his new tent and the prayer of the Prophet.

An Anatolian Turkmen black tent, Sachikara tribe, Kahramanmarash, Eastern Turkey, Pjoho courtesy, Josephine Powell, early 1980s Suna Kıraç Foundation

The legendary Turkmen tents seem to be more and more rare these days but it seems, on the other hand, that the legend will somehow continue to live in the Anatolian steppes for a long time.