Handwoven Carpets of Turkey – 2 Central Anatolia

November 19, 2020

Travelling To Turkey After The Pandemic, Impressions Of An 85 Years Old German Ethnologist

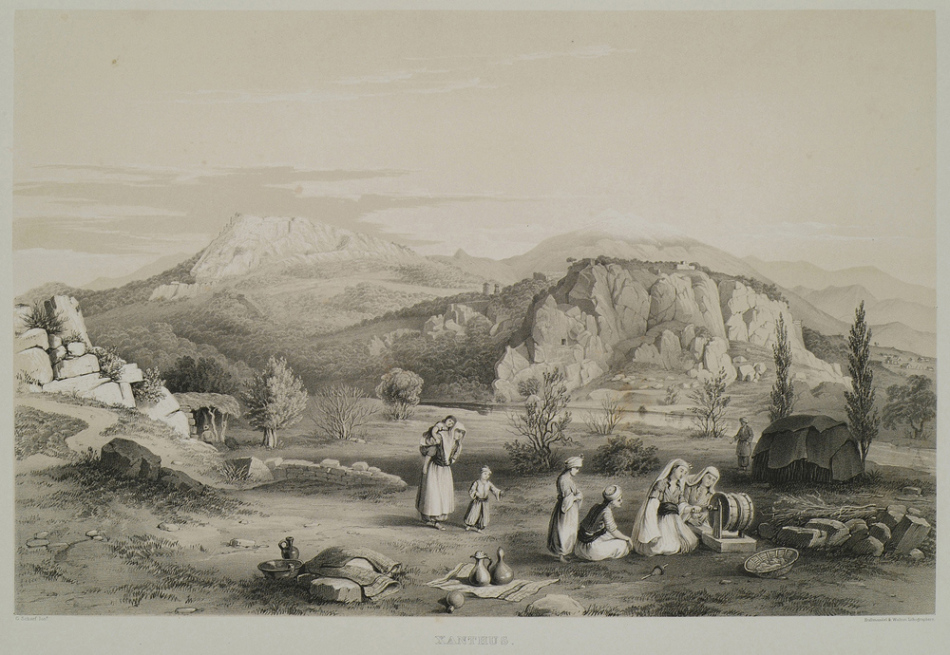

November 10, 2021Western Anatolia is a very special place in Turkey, which combines the Hellenistic culture and the Turkmen culture on the same ground. The area is relatively warm in terms of climate and low in altitude, and is divided from north to south by several big valleys and plains in which important rivers flow.

Aegean valley surrounded with mountains, Western Turkey

The area is roughly surrounded by the steppes of Central Anatolia in the east, Western Taurus mountain chain in the south, the Aegean Sea in the west, and Marmara inner sea and Ida mountains in the north.

The area had developed an important weaving culture in archaic times. The fabrics and rugs produced in Lydian and Phrygian lands were famous in the whole of Aegean civilizations, as well as the wool quality and colorful dyes of Laodicia, nearby today’s city of Denizli.

Reproduction of a Phrygian fresco found in Western Turkey showing the clothing of women at that period in Phrygia

After the arrival of Turks in the area the Turkmen dynasties of Karesi, Aydın, Saruhan, Menteşe, and Germiyan were the primary political and economical powers of Western Anatolia. Turkmens linked to these confederations were residing in the deep valleys and plains during the winters and were going to the inner parts of the area such as Afyon, Uşak Denizli, Tavas, Kütahya, and Eskişehir for the summer to practice sheep husbandry in those elevated and cooler places.

Turkmens in Fethiye, Western Turkey, Gravure by Georges Scharf 1847

A Turkmen grave stone having the tribal sign of the “Salor” tribe engraved, 13th century, Denizli, Western Turkey, photo by Ümit Şıracı

Two Tahtacı Turkmen ladies posing for the hıdrellez holiday, Tahtakuşlar, Balıkaeisr, Western Turkey

The local carpet production workforce of Turkmens had been unified by the Ottomans after the Ottomans had established a steady socio-political structure in the area. The main aim was to build a cottage industry and state-controlled carpet production sector which would bring important amounts of money from export. There were all of the advantageous factors surrounding the area, like the Anatolian Turkmen workforce, experienced enough spin the yarns needed and to weave beautiful carpets, the high-quality raw materials such as high-quality wool, enough empty place, and suitable climatization to make dyestuff agriculture, and the closeness to the sea for the sea-trade issues.

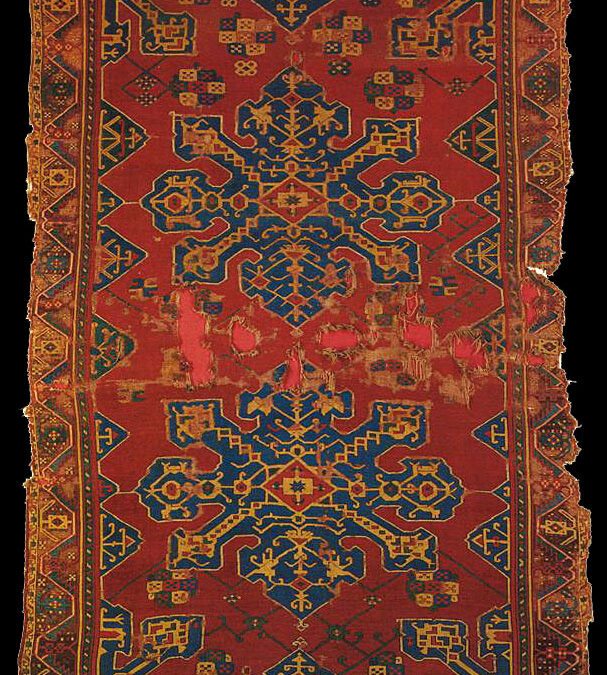

14th-15th centuries, Crivelli patterned carpet, Western Anatolia

So called Holbein carpet 15-16th centuries, Western Anatolia

14th-15th centuries, Crivelli model carpet, Western Anatolia

Early Western Anatolian workshop carpet, 15th century, National Carpet Museum, Tehran

One of the important branches of the silk road ends up in Smyrna Port on the very west end of the area. This road had the capacity to bring the produced carpets from the inner parts of the area, and even from the other Areas of the Ottoman land such as Konya carpets or Cairo carpets. On the other hand, the experienced Turkmen workforce was ready to weave even the most complex patterns in the best way possible. Another important factor was the raw materials or semi-finished products such as the high-quality wool or spun yarns of the dye plans collected or cultivated in nearby valleys.

15th century Western Anatolian carpet, from former Kirchheim collection, Doha

15th century Western Anatolian carpet, from former Kirchheim collection, Doha

Bellni patterned workshop carpet 16th century Western Anatolia, Ballard Collection, Metropolitan Museum, New York

Bellini patterned workshop carpet 16th century Western Anatolia, Islamic Arts Museum, Berlin

With these developments, the classical carpet schools named of Ushak, Manisa, Selendi, Gordes, Kula, Melas, Dazkiri, and Bergama were formed. The patterns were mainly created and distributed by Nakkaşhane-yi (Hümayun the court design workshop,) mainly deriving the carpet patterns from the classical tile or book tome patterns. On the other hand, the production quality was surveyed by the supervisor and financed by the Ottoman court itself. Thus this area has been a very well known and appreciated area by of different weaving schools or styles. Those styles or patterns were painted by several painters of the Renaissance period, and are named after those painters or the area that the carpets are continuously sold to, such as Lotto, Holbein, Crivelli, Bellini Transylvanian rugs.

Ushak carpet, 16th century, having the pattern and the weaving from local workshops, Private collection, Palazzo Lomellino; Gevova/Italy

Lotto type of Ushak carpet, designed and woven in workshops of Western Anatolia, 16th century, Victoria and Albert Museum / London

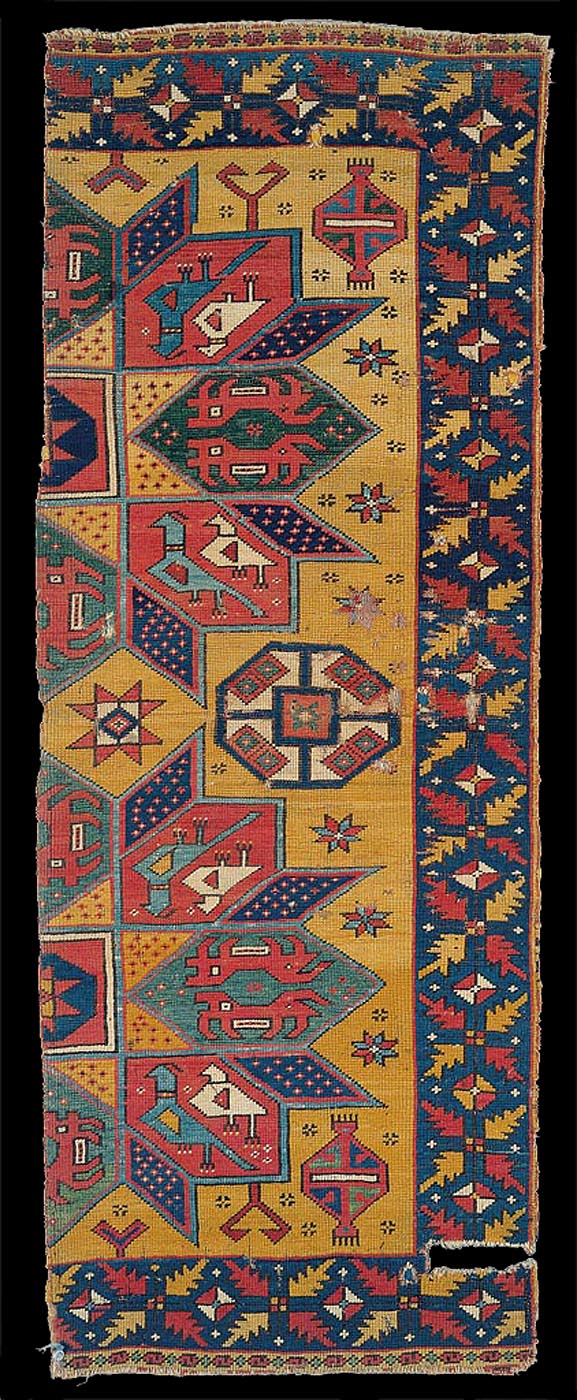

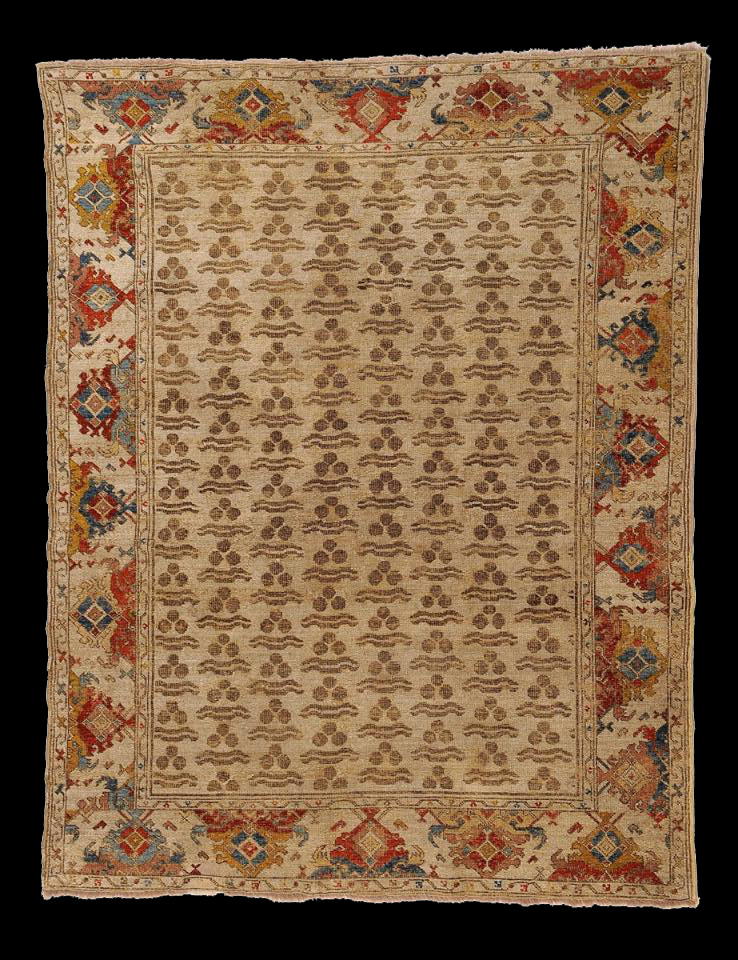

So-called “bird Ushak” patterned carpet, 16th century, Vakiflar Museum

The comparison of a bird Ushak pattern with Turkish tale drawing taken as the source of the pattern of the same period, 16th century

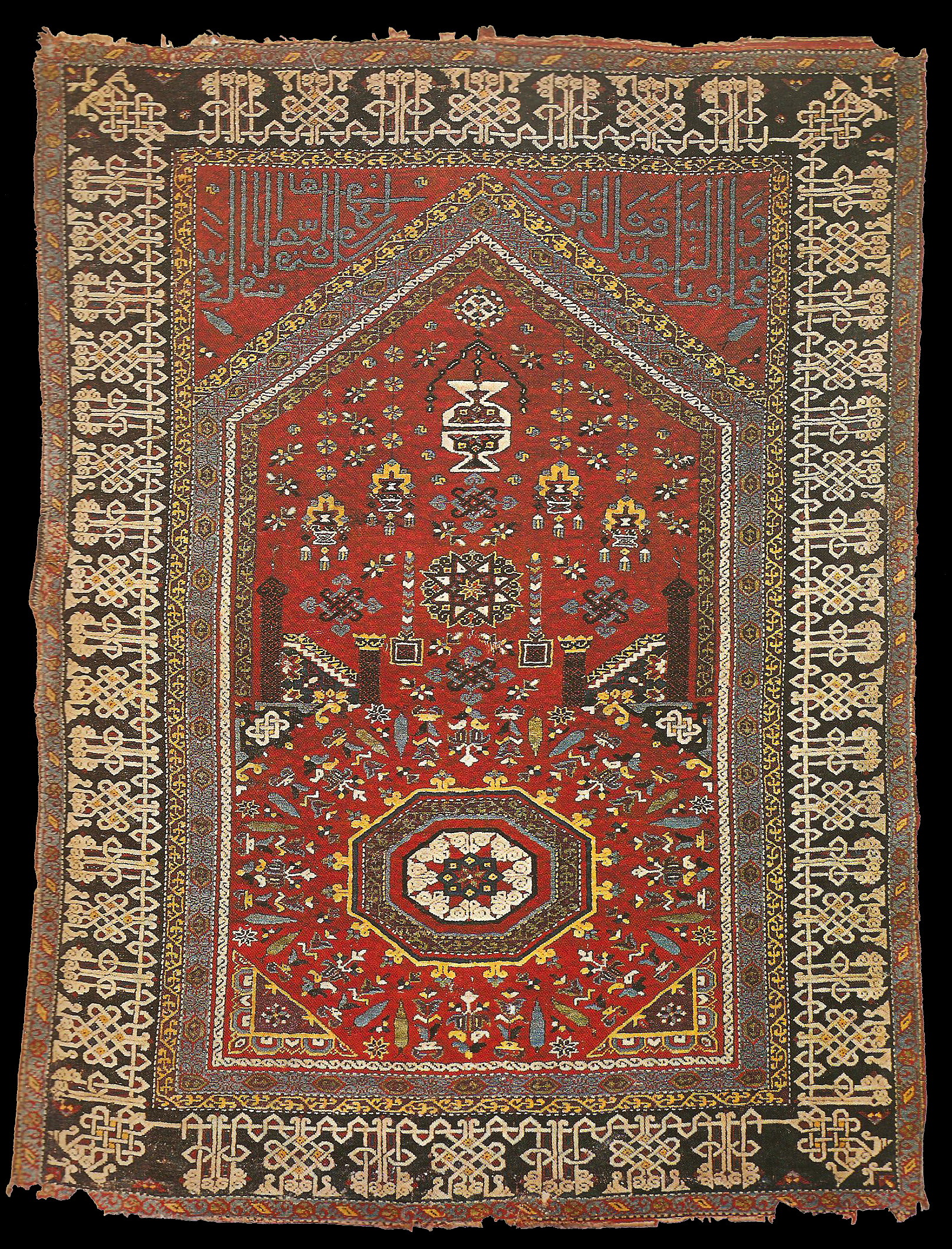

Transylvanian type of Western Anatolian workshop carpet, 17th century, private collection

Transylvanian type of Western Anatolian workshop carpet, 16th century, private collection

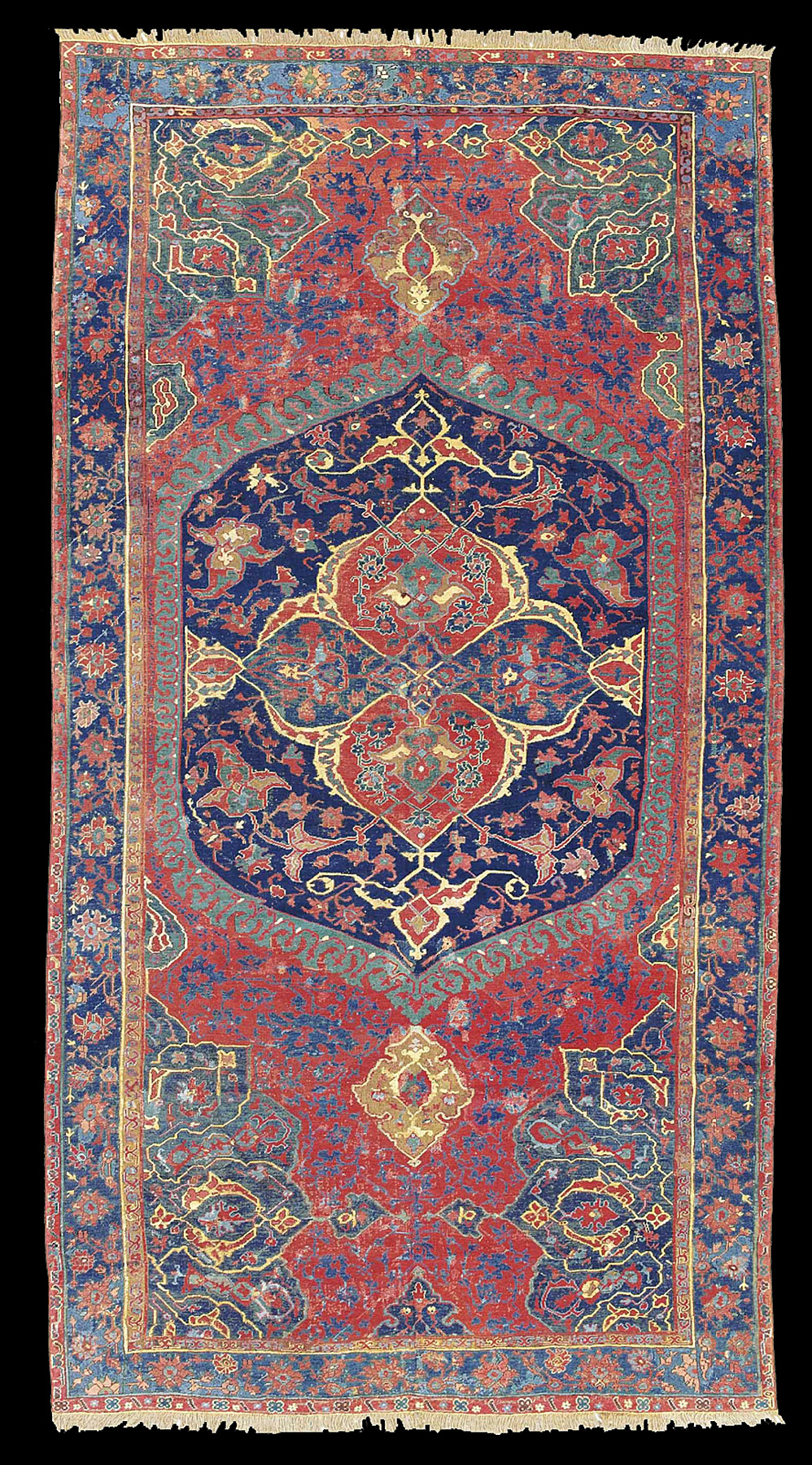

Medallion Ushak carpet of 16th century workshop production, private collection

Holbein carpet, 17th century, Vakiflar Museum

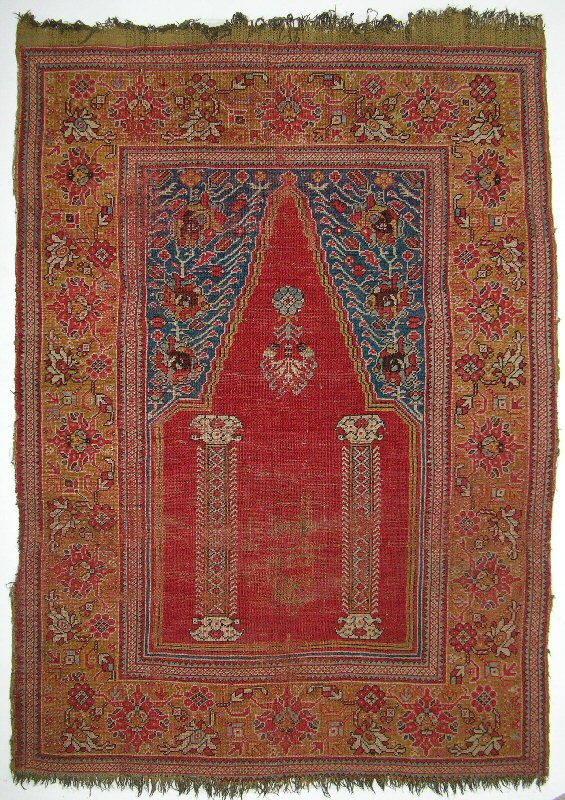

Bellini Carpet, 16th century, Western Anatolia, private collection

There was also a re-Turkmenization of the patterns which were designed only for the European market, by the retired weavers going back to their personal looms and who interpreted the patterns according to their own taste and without using a pattern cartoon. This effect can be described as ruralization or even tribalization of the urban workshop-designed carpets.

18th century Western Anatolian workshop carpet, Vakiflar Museum/Ankara

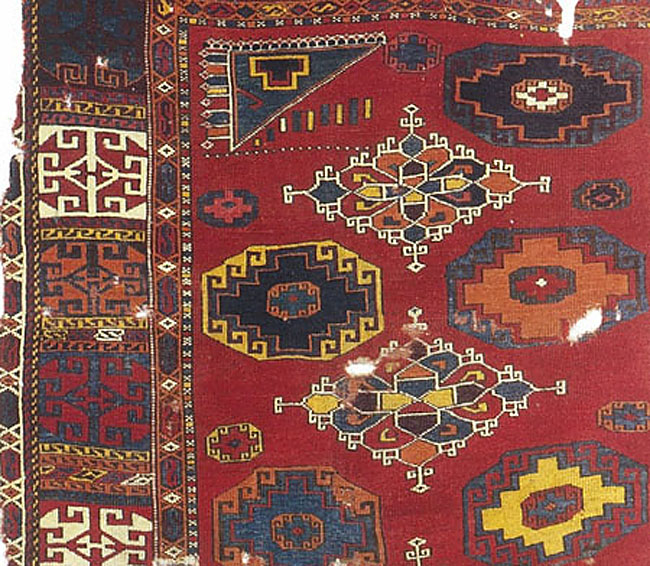

Antique Bergama Tribal carpet of Karakeçili Turkmens, mid-19th century interpretation of the carpet pattern on the left, private collection

An antique Bergama village carpet, 18th century, private collection

A 17th-century Selendi Workshop carpet, Western Anatolia, private collection

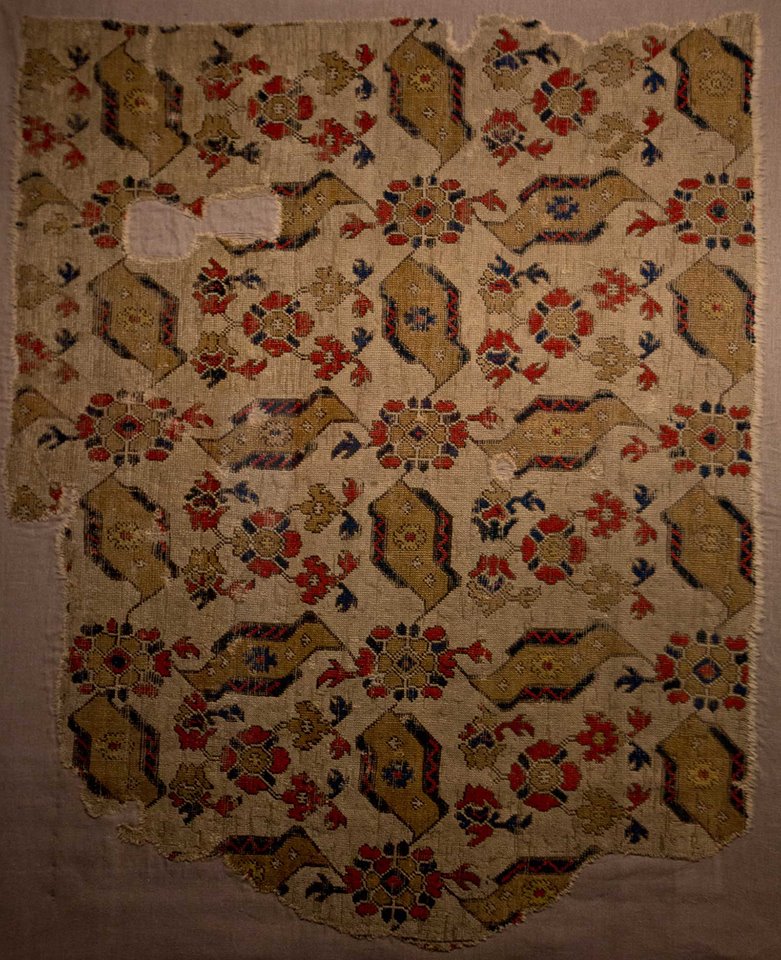

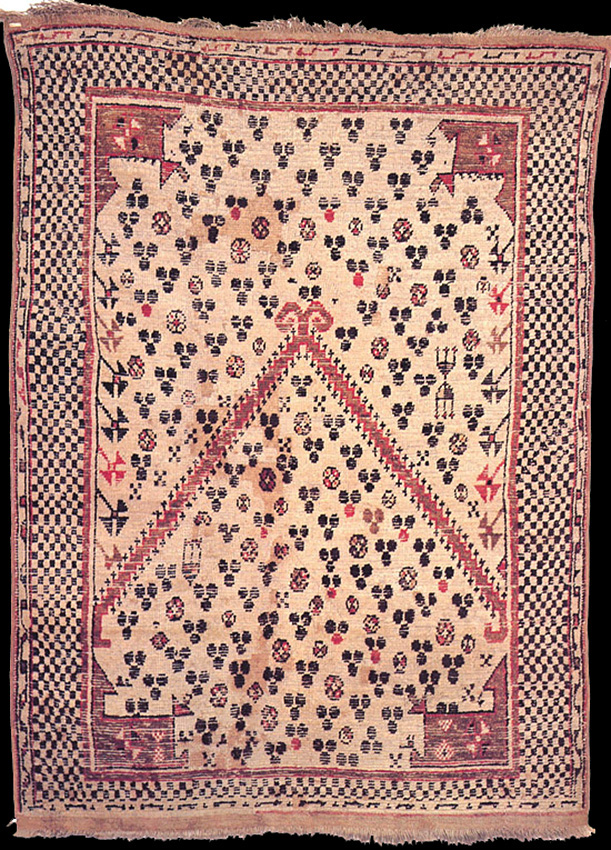

A rural interpretation of Selendi workshop carpets in the same area in 16th century, Museum of Applied Arts / Budapest

The commercial export carpet production took place in the area from the early 15th century until the late 19th century, then moved to the northern areas by the effect of the Industrial Revolution and the developments around it. These areas as Gördes and Bandırma (Panterma) were economical production centers of the Western Anatolia for two and a half centuries.

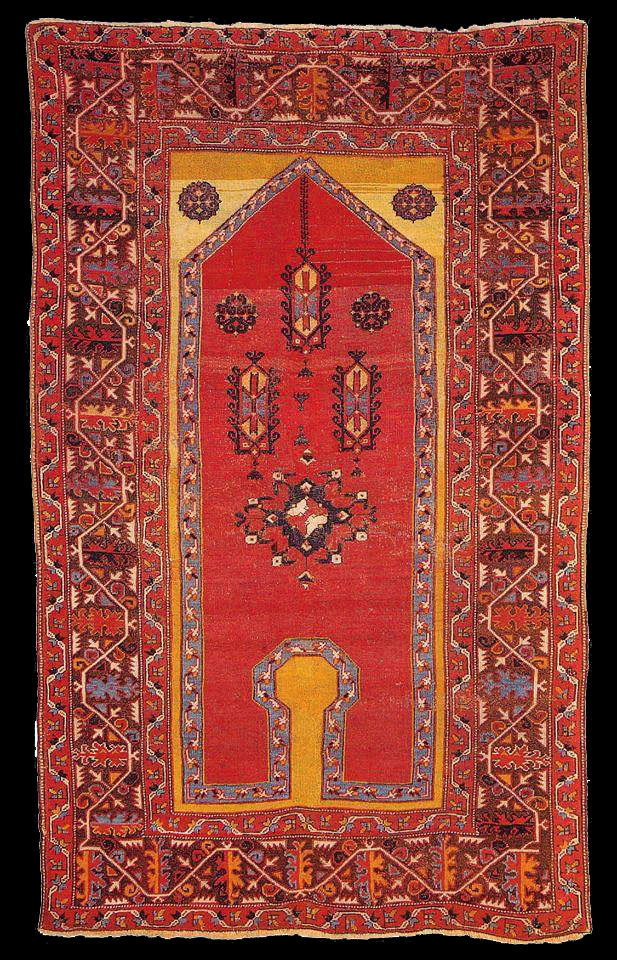

Gördes workshop carpet, 18th century, Western Anatolia, Vakiflar Museum / Istanbul

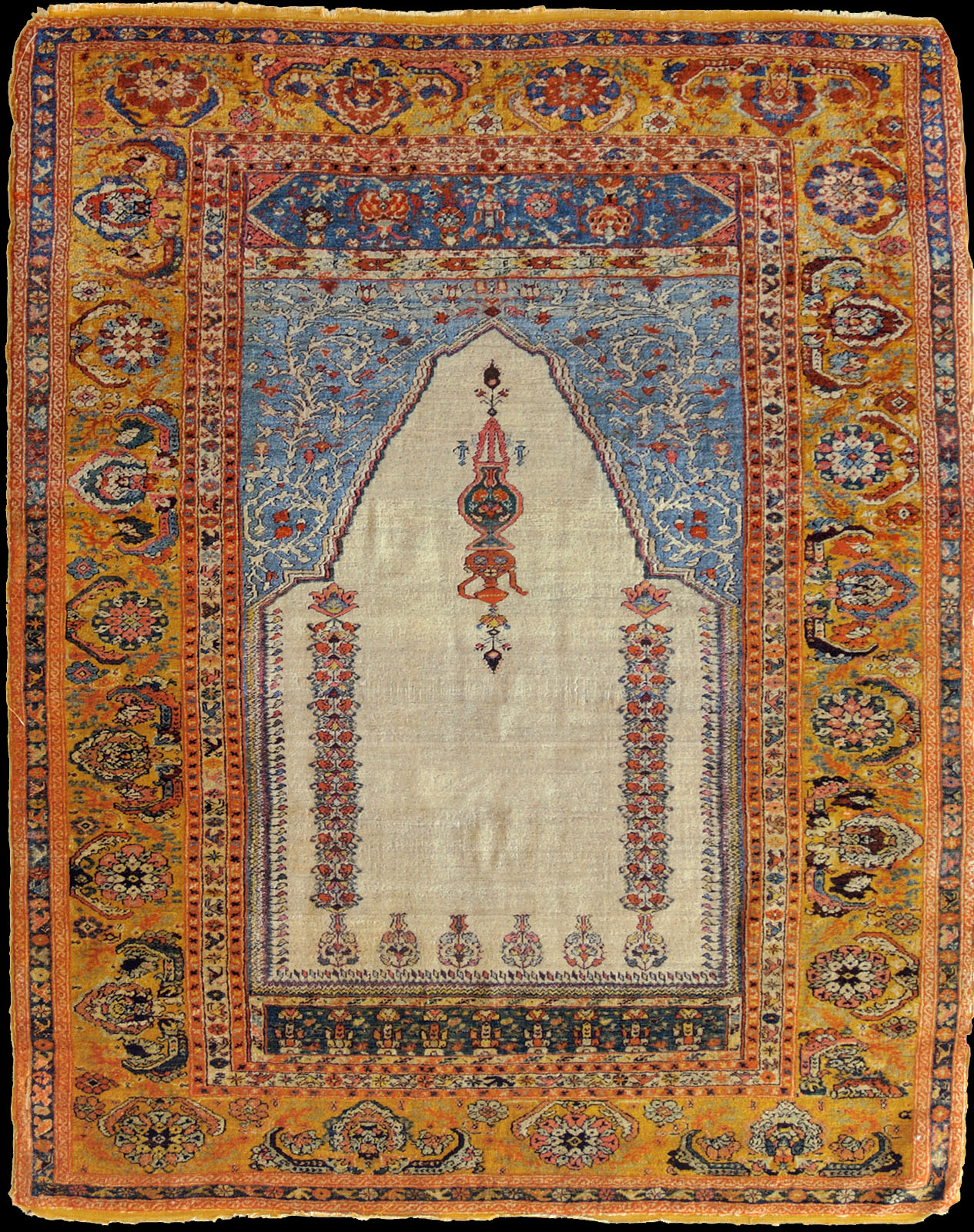

Bandırma workshop carpet, 18th century, Western Anatolia, private collection

The Western Anatolian carpets have shorter pile, a dense weave, and very developed and very diverse patterns and colors. The wool is a bit dull and waxy. The professional carpet producers benefited from this property of the yarn to emphasize the saturation of the dyes and create contrasts between dark and light colors in this way. Mid to light madder reds, mid blues, grass and very dark teal greens, and light to dark yellows are used. The 16th-century classical Ushak color palette may have the most developed and highest quality color palette of the whole Anatolian carpet production activity.

Antique Bergama Carpet, 18th century, private collection

Antique Bergama Carpet, 18th century, private collection

An early star Ushak carpet, 16th century, Western Anatolia, Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum / Istanbul

17th century Lotto type Ushak carpet, Western Anatolia, Staatliche Museen zu Berlin / Berlin

The close-up structure of knots and the pile of the same carpet

The positioning of the knots and the semi-deppressed warps from the back of a Lotto carpet from the same period

An antique Bergama village carpet of the 18th century, The Metropolitan Museum or Arts / New York