Interact With Locals, Collecting Memories on The Nomad Way – Turkey

November 17, 2020

Trekkers, what to eat while migrating on The Nomad Way – Turkey

November 18, 2020The Anatolian Peninsula has been inhabited by Turkic tribes since the early 11th century. During the decline of the Seljuk Empire in Iran and increasing Mongol pressure coming from the East, Turkmens (which means a group of Turkic-language-speaking tribes converted to Islam and who live in Western Asia) moved to Anatolia and took refuge under the reign of Seljuks of Anatolia.

Turkmen warriors in a small encampment, miniature of Mehmet Siyahkalem 14th century, Topkapi Palace Archive / Istanbul

From the beginning of this period, we see Anatolian carpets in terms of knotted pile carpets first woven in Anatolia by the efforts of the Turks. The first carpets that we find in mosques remaining from the Seljuk period are generally extremely large, very coarse, with a few colors, and always with repetitive patterns. From those common properties, we can deduct that those carpets were not homemade, because they are much bigger than carpets that are possible to be woven within the house conditions. That also means that Seljuks were financing those carpets to be used in municipal buildings such as palaces, madrasahs (medieval Islamic schools), or mosques. The main aim of those carpets was not to embellish the entourage but to provide insolation of those buildings from the cold. Also, the coarse structure emphasizes the need for speed in the weaving of those carpets, so the carpets should be ready for new buildings financed by Seljuks when the buildings were ready to be occupied.

Seljuk carpet, 14th century, Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum / Istanbul

Seljuk carpet detail photo, 14th century, Turkish and Islamic Arts Museum / Istanbul

The repetitive pattern structure taken from the ornaments of Central Asian exterior brick building facades do not have any shamanistic meaning, and were most probably designed on purpose. Seljuks had a very deep concern about providing their subjects who recently became Muslim a strict Sunni type of belief, in which shamanistic traits should be erased.

After the collapse of the Seljuks at the beginning of the 14th century, we see the triumph of local seigniories which had a closer lifestyle to and policy toward the nomads and nomadic life. We see the Anatolian carpets becoming much smaller and nearly always in the size of a prayer rug, not necessarily with a prayer niche but with other mysterious animals depicted. This is definitely the effect of nomadic life, in which state-controlled carpet production left its place to the individual carpet production, either in cottages or nomadic tents with much finer weaves and a lot of animal-style patterns such as dragons, phoenixes, sacred deers, and many other creatures that have a meaning in shamanistic belief.

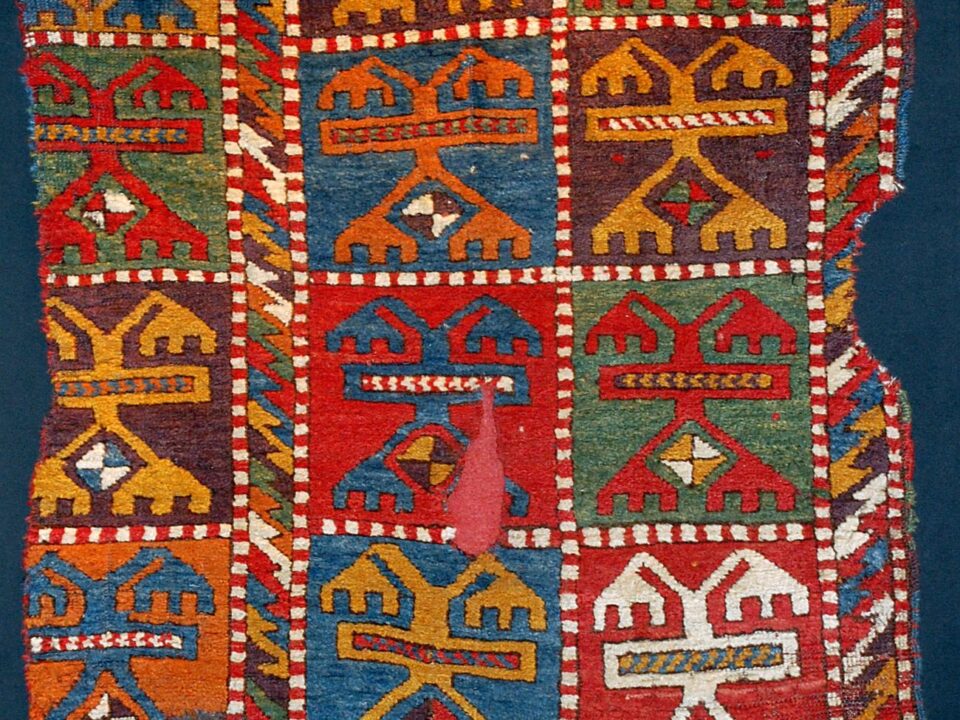

Detail of a 14th century animal style carpet, Central Anatolia, Vakiflar Museum / Istanbul

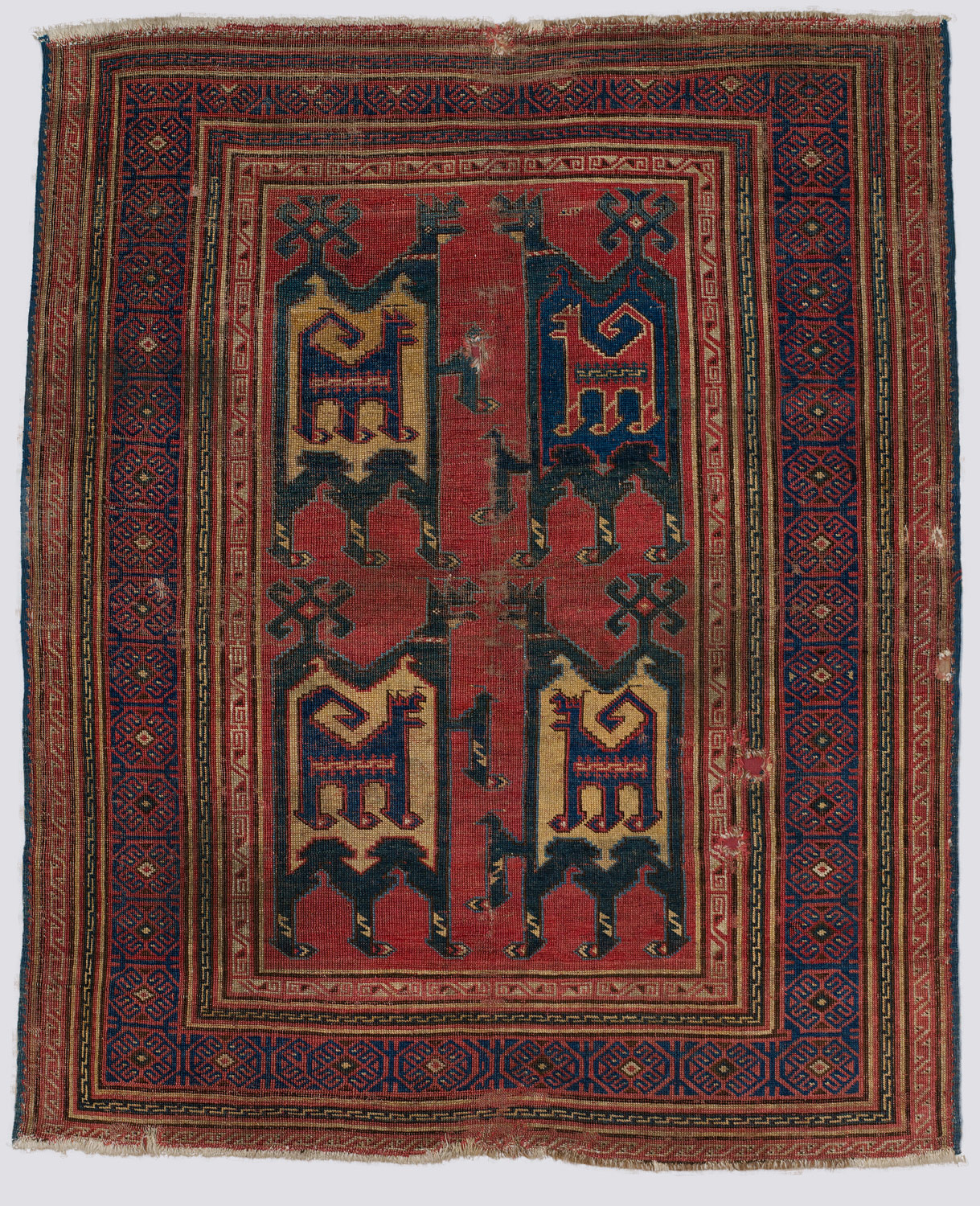

Turkish animal carpet, 14th century, Metropolitan Museum /New York

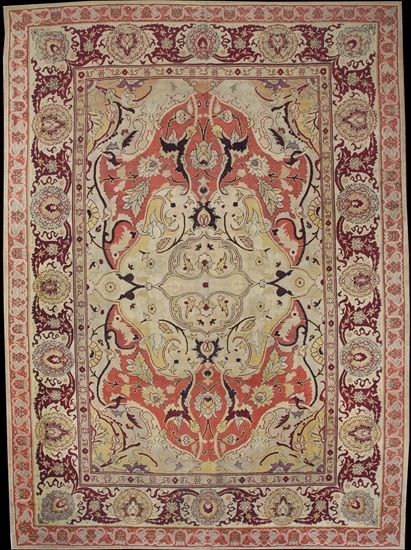

At the beginning of the 15th century, we see Ottomans establishing a stable system. This system provided Turkmen Tribes the ability to settle in the western Anatolian valleys and partially practice animal husbandry like their ancestors. With carpets known as diplomatic gifts, Ottomans began to finance and supervise carpet production in Western Anatolian towns such as Ushak, Gördes, Kula, Demirci, Simav, Selendi, and others. All of the positive factors, such as an experienced Turkmen spinning and weaving workforce, sheep and wool, dye materials, and one branch of the Silk Road leading to Smyrna were there. So Ottomans transformed the cottage industry to a state-monitored workshop industry and gained huge amounts of money from the exportation of those carpets. The imperial design workshop was also involved in this production operation and created some very beautiful patterns based on tile or bookbinding patterns such as medallions or spandrels. Those patterns would influence Turkmen rural production of carpets and kilims, but also some weaving schools in Iran, Syria, and the Balkans with mostly the designs but also with the colors and weaving techniques. So-called Transylvanian rugs are the fruit of this vast operation of state-monitored production in Turkey/Anatolia that lasted for several centuries. We do call this period the Classical Period of Turkish carpet production. In that period some carpet designs painted by Renaissance painters have taken the names of those painters for their classification. Holbein, Crivelli, Lotto, Bellini carpets are the famous ones in that type of classification.

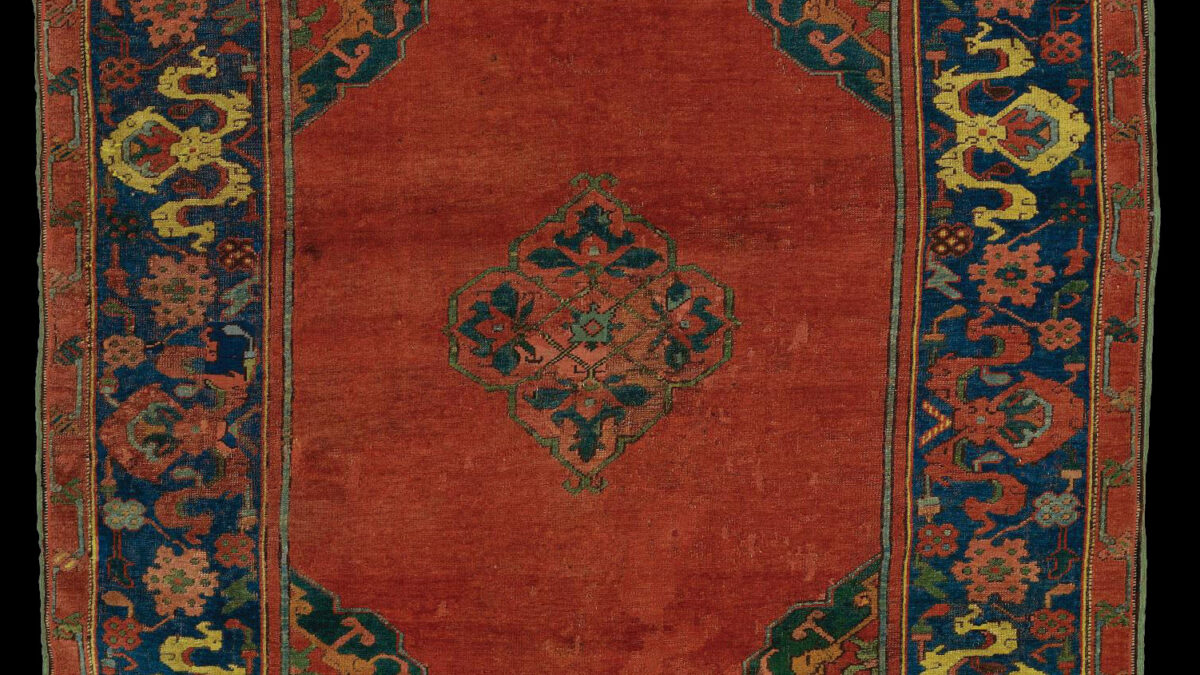

Transylvanian carpet, 16th century, Western Turkey, Private Collection

Classical Ushak medallion carpet, 16th century, Private collection

Small mediallion, Ushak carpet, prayer size, 17th century, ex Rudolf Martin collection

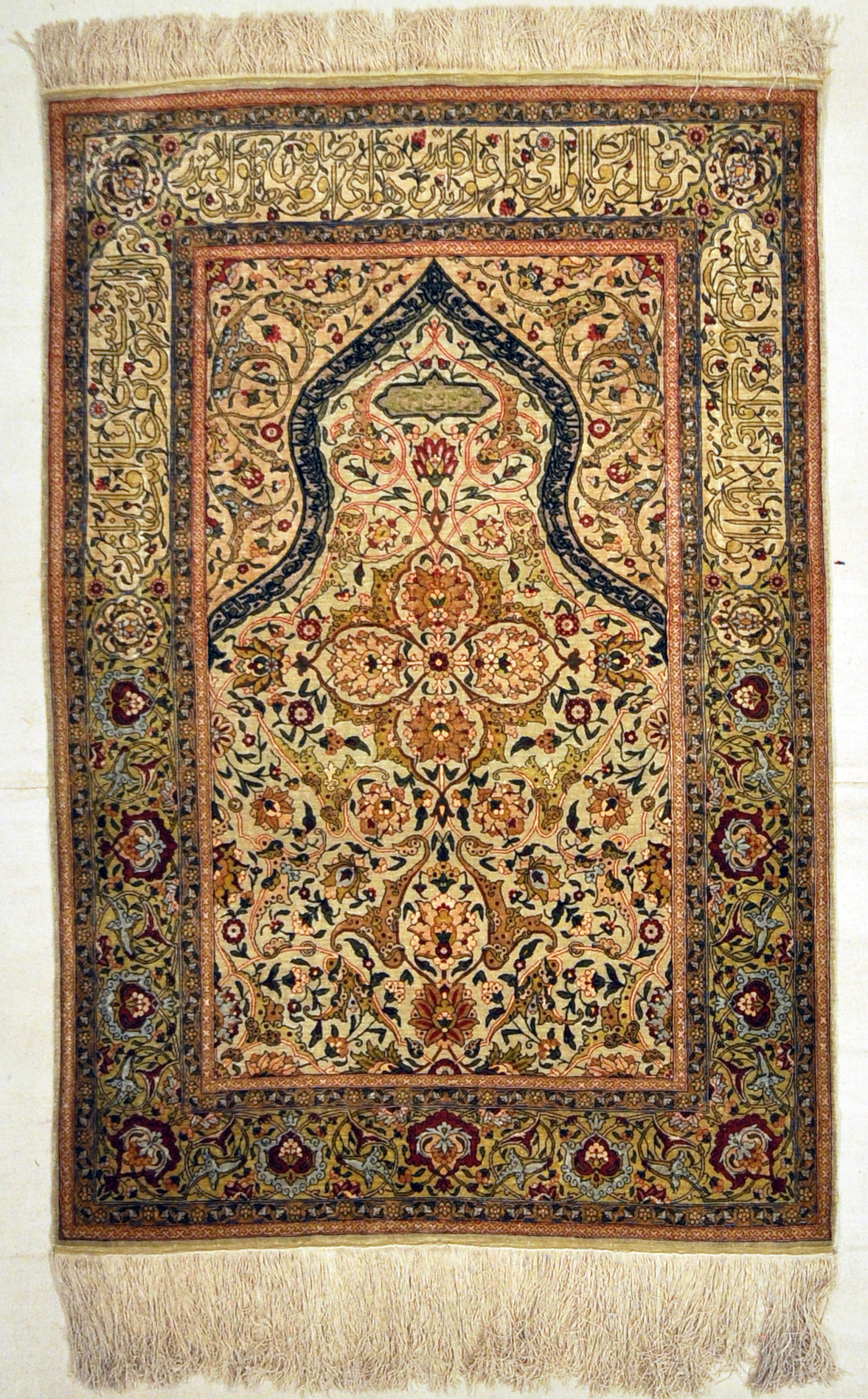

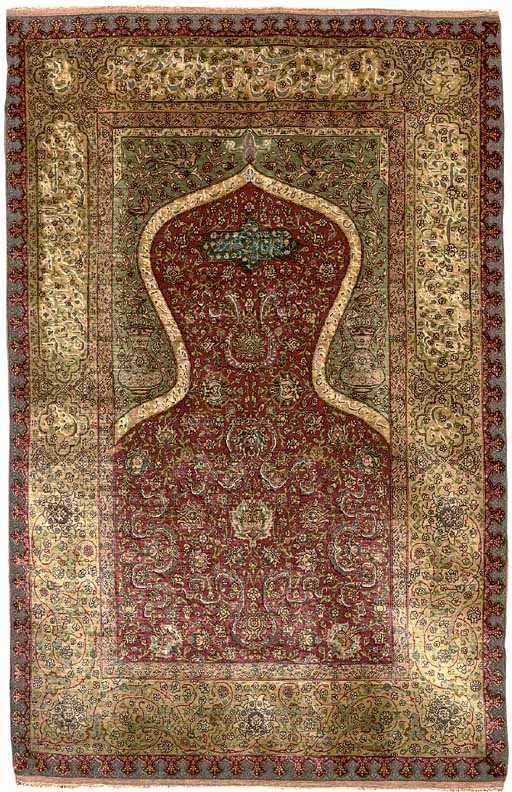

Towards the late 18th century, the industrial revolution began to show its effect on the Ottoman Empire and Ottoman art. The classical patterns were attempted to be modernized, the natural dyes began to be abandoned for the new chemical ones, especially after the 1870s, and machinery began to show its effect on mass production, such as the spinning of yarns. After the mid-19th century, we see a more centralized carpet production being closer to the machinery and accumulating around the capital city of Istanbul. Individualism and freestyle applied by the weavers in a limited but harmonious way disappeared totally in this period. The finesse and the regularity of a carpet began to be more important than the color balance and the freedom of the pattern. First, revolutions seen in Gördes were followed in closer and closer production locations to the Ottoman palace in a succession, such as Bandirma, Hereke, Kumkapı, and Feshane, just because the carpets were more and more expensive objects that only the members of the Ottoman court and their entourages were able to afford. Nearly all of the production going on in those locations was subjected to Ottoman court oversight, and to no one else.

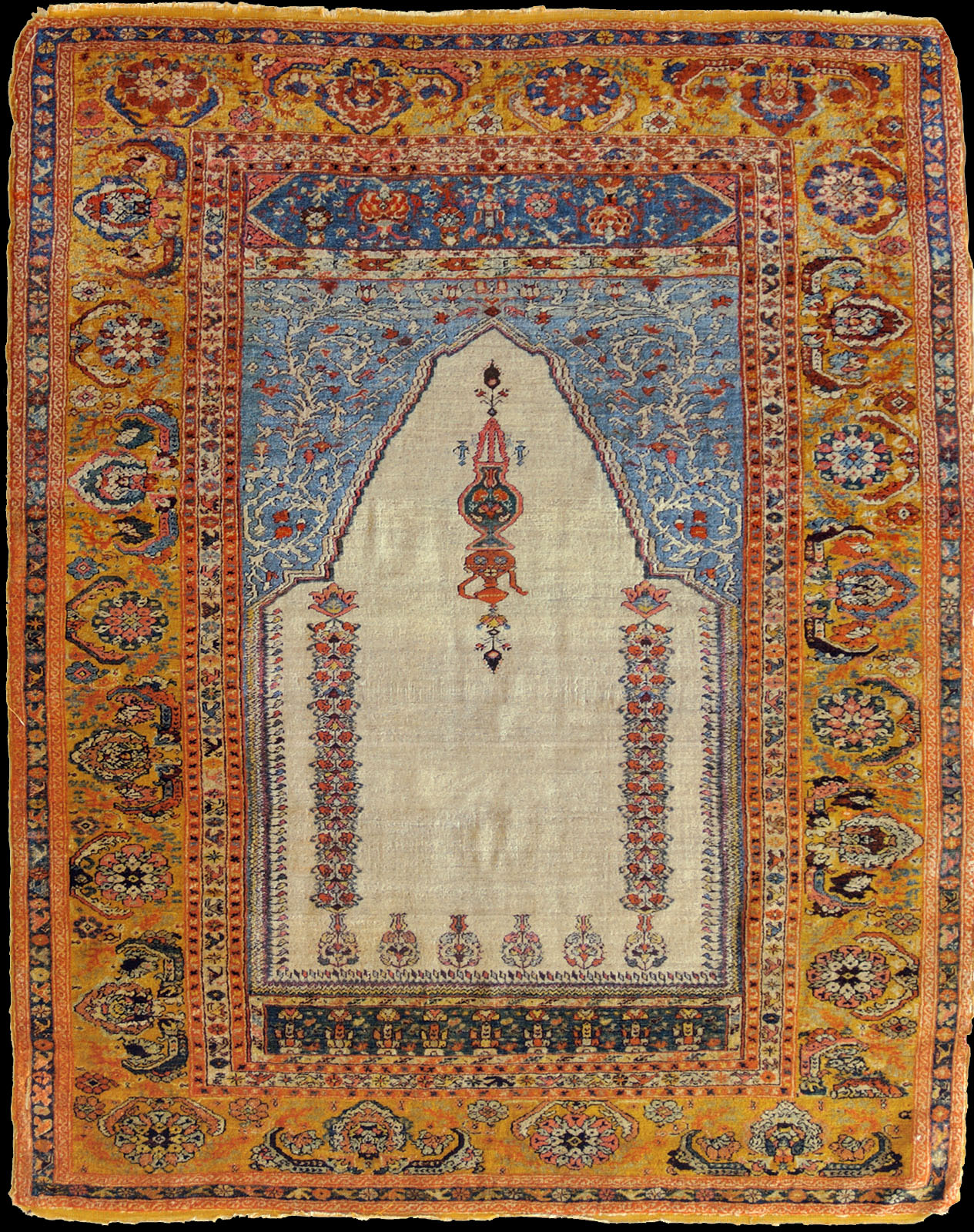

Gordes carpet, late 18th century, Western Turkey, Private collection

Bandırma Carpet, Late 18th century, North-Western Turkey, Morandi Carpets / Italy

Hereke Carpet, late 19th century, northwest Turkey, Private collection

Kumkapı Carpet, early 20th century, Istanbul, Private colleciton

Feshane Carpet, Early 20th century, Istanbul, Private collection

After the collapse of the Ottomans in 1923, the New Republic tried to protect the still-ongoing factories in Hereke. The Feshane carpet factory was already closed and Kumkapi was an ensemble of small private institutions. The official bank (Sümerbank) owned and financed workshops and operated until the end of the 1990s, but neither the supply nor the quality of materials was enough to keep up with both the domestic and foreign demand for high-quality carpets.

Sümerbank-State production carpet, the 1980s, Private collection