Colors through eyes and hands of Anatolian weavers

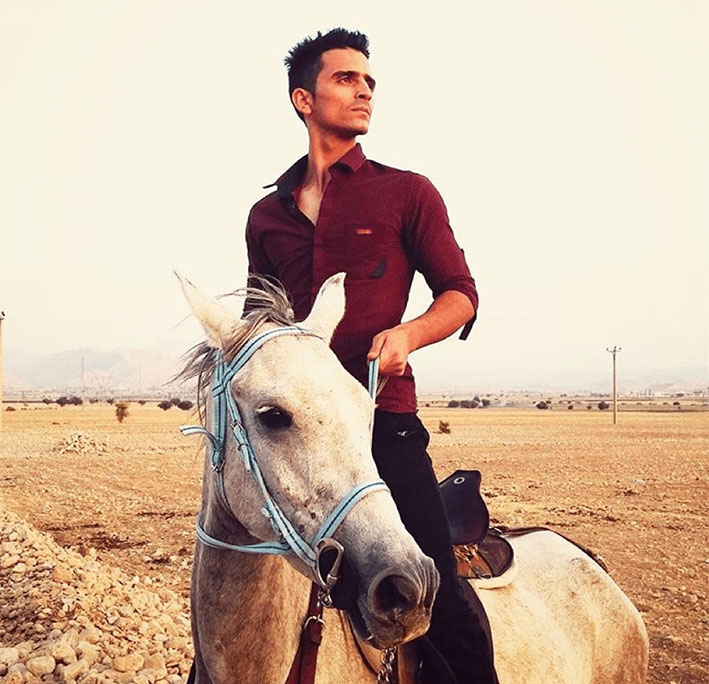

May 11, 2020This is Reza,

Reza is a member of Qashqa’i community. Qashqa’i people are one of the most well-known nomadic tribes of Iran. They have been known for their bravery and strength. They speak a Turkic language and still keep their nomadic life in south west Iran.

We have never met Reza in person, but our common love of Turkic culture and nomadic life drew us together in a very warm and sincere way.

Reza lives in Gachsaran town of Esfahan city, populated by Lor and Qashqa’i tribespeople. The family of Reza left the nomadic life and settled in Gachsaran town twenty years ago; before, they were migrating between the high mountains of Esfahan region and the low plateaus of Abadeh city in the south of Iran.

When I told Reza about the idea of making the revival tour of nomadic life, he was more than happy and said that he was ready to support us with any kind of help possible. Well, we were in the stage of researching information about the famous goat skin water bags of nomads in order to make one, because not only are these water skins extinct but the masters in Anatolia, who were making the tanned skins, had stopped producing them many years ago, or had already passed away.

So we asked Reza how to make a tanned skin container in order to carry drinking water. He immediately asked his mother who is a very talented weaver, wool spinner, and dyer, but also a person who knows how to obtain leather from animal skin as many Qashqa’i tribeswomen do.

The recipe for the process arrived immediately and we begin to search for a goat skin to be freshly obtained from the animal. In the following days the telephone rang and it was Reza on the other side. He said that his mother told him “it is difficult for your friend in Istanbul to make it but it is easy for us, let us make two for him and you will send him these water skins as a present for his new job.”

I was more than happy; touched by the sincerity of their heart I was in tears. In the following days, Reza sent me some photos of the skin becoming leather day by day. And finally the preparation of water skins was finished. But we had a big problem: How to send them to Istanbul! In customs, officers who check the content of the cargo packages coming from abroad leave known and defined objects such as books or shoes after passing them through X-ray machines, but a water skin with an empty inner part that could contain any material? So most probably they would pierce the skin to see if something was hidden inside.

We couldn’t come up with any other idea than to smuggle the skins into the luggage of a known person so that we could have them in our hands without any damage.

I called one of my friends, Aytaç, who is a drama teacher in Van city, near the Iran border to check if he has an acquaintance who conducts trade between Van and Urmiyeh, two close cities 300 kilometers apart, one being in Turkey, and the other in Iran. He said he had a friend from Urmiyeh whose uncle was a merchant between Urmiyeh and Van, so that our Qashqa’i friends would send the skins to this Kurdish family living in Urmiyeh and their uncle would bring the skins to Van in his luggage.

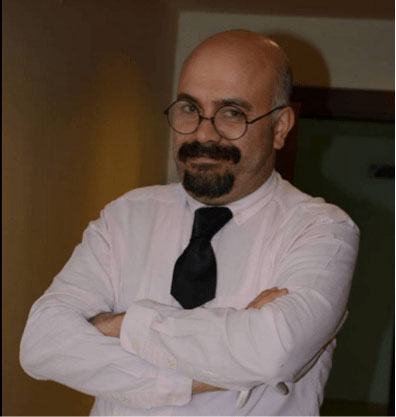

(Aytaç, my friend from Van)

As promised, the skins were sent to Urmiyeh, but they must be filled with fresh water regularly every two or three days in order to prevent them from cracking. So, a lot of work! Moreover, the uncle of the family refused to carry the bags across the border so that we all have been stayed desperate and sorry, without knowing anything to do to resolve the problem.

But one night……. One night Aytaç, my drama teacher friend, received a phone call from a remote village near Van, just neighboring the Turkey-Iran frontier. The man on the other side of the phone was saying “Our respectable teacher, your custody object has been brought to our village from one of our relatives from the other side of the border. We are members of the Herki tribe, you can trust us, please be assured.” The man continued by saying “We have controlled the skins during transport, and if they have been damaged during the journey, we would make them here in our village from scratch, because a promise is a promise.” Aytaç, impressed by what happened, told me about the story with tears and sent the package to Istanbul. In fact the Kurdish family, whose uncle refused to carry the skins, found a smuggler from their tribe, which has many villages in the Van region. They gave him the skins and the telephone number of Aytaç, and paid him some money, and the man brought the goatskins via donkey back, through a walkway in a mined forbidden area and delivered the skins and Aytaç’s phone number to the chief of this remote village. The man who called Aytaç was this village’s chief. I was in tears for the second time for these skins. They were worth a treasure for me, and more!

(Mountains from which the smuggler brought the skins in donkey back)

Now I use them in my tours with pride, love and gratitude. Each time I touch and drink water from them, I remember my friend Reza and his lovely mother; Aytaç, my friend living in Van; and this family from Herki Kurds that I had no chance to meet, but may one day; this smuggler who put his life on the line for a promise; and this village chief who showed the initiative of checking the skins’ state and who was ready to make two more if they would be damaged. What to say? The world is continuing to turn due to the actions of these warm hearted, honest and honorable people!

Uncle Dursun, the Tent Maker.